✱

Last updated:

No commit data found.

Today, it is

The Hidden Beauty of HashLife

September 4, 2024 • 13-19 min

I was introduced to Conway's Game of Life from Daniel Shiffman, particularly in his mini-series about cellular automata. For those who are unaware, Conway's Game of Life was the product formed by rules devised by John Horton Conway in 1970. Despite its name, the Game of Life is a "zero-player game" where the game progresses without any player input. If anything, it's more appropriate to call it a "simulation".

Given a 2D grid, each cell can either be alive (1) or dead (0). What determines whether they live or die at each iteration are determined by the rules of the game.

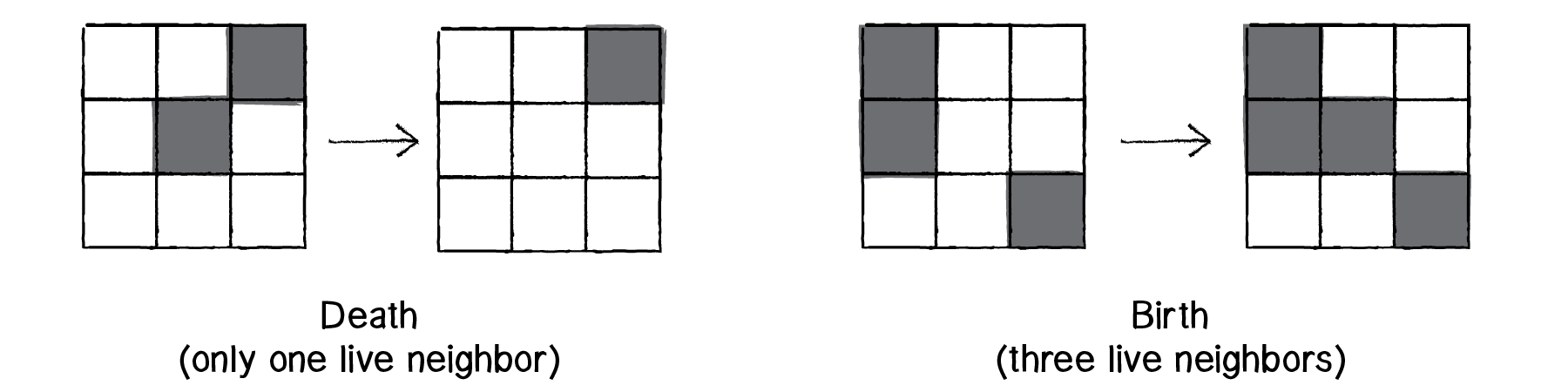

The rules are as follows:

- Any living cell with less than two live neighbours dies ("underpopulation").

- Any living cell with more than three live neighbours dies ("overpopulation").

- Any dead cell with exactly three live neighbours will come to life.

- All other cells remain the same ("stasis").

To initiate the game, a configuration of cells in any shape, form, etc. is placed on the 2D grid. For each generation, the cells apply the above rules, changing their configuration throughout time.

It is undeniably a compelling thought experiment, as it proves that organization can emerge from a universe governed by very simple laws. Our civilization, culture, and species may very well be a result of eons of configurations that seem amorphous in nature, but can form meaningful constructs given a starting point & time.

For my implementation, I've decided to create my own simulation of Conway's Game of Life. The application was written in Typescript + React and built with Vite. I've also implemented the main update loop with the HashLife algorithm (quadtrees & memoization), which we will discuss more thoroughly later in this article.

Currently, it supports edit mode, infinite canvas, zoom & pan, pattern import, and step size & speed. You can play with it yourself through this link.

Besides the introduction, the crux of this article will focus on Bill Gosper's HashLife algorithm, where we will discuss the definition, properties, implementation, and the hidden beauty that emerges from it.

What is HashLife?

Simply put, it is a memoization algorithm to compute long-term fate of a configuration. For instance, you can quite easily generate a 6,366,548,773,467,669,985,195,496,000 (6 octillionth) generation of a Turing machine in Life.

If I were to give it a more descriptive title, one that explains exactly what it accomplishes, it would be: "Exploiting Regularities in Large Cellular Spaces".

In all walks of life, redundancy is everywhere. Whether you wake up in the morning to brush your teeth, or meeting up with the same clique of friends, or even communing to work, we carry ourselves through the "ordinary". Our brains can even remember when we've done something again, such as when we encounter a hard math question that we've studied the night before, or learning a new language, and we can use our memory to guide us towards the answer.

Through redundancy, we can achieve memory, and through memory, we can arrive at the solution with less time & resources from the first time we've attempted it.

In computer science, this principle holds true. We use code to automate everything in our lives, because a computer can tolerate the endless repetition of a task. But, if we allow the computer to remember a task, the computer can more efficiently arrive at a solution much like humans.

When iterating through each generation of Conway's Game of Life, there will be some sections of the grid that have recognizable patterns. For example, the Breeder 1 is composed of multiple Gosper glider guns, which can then generate smaller spaceships.

In fact, most large & complex configurations are mostly smaller configurations working in unison, so if we can somehow "remember" how a portion of it changes, we can assemble these changes back up to the large configuration, effectively updating the configuration entirely.

To summarize, we need to:

- Break down a configuration to smaller, recognizable configurations.

- Remember the state of that configuration, and quickly arrive at the changed state of that configuration.

- Reassemble the original configuration through these smaller resulting changes.

For the first step, we will use Quadtrees. For the second step, we will use memoization. And finally, the last step will be accomplished by using these two strategies to build up to our final solution.

Algorithm

For a more general overview, the algorithm stores subpatterns (we will refer to them as "subgrids", or even nodes) in a hash table (like a "cache"). Then, we memoize future iterations at various locations on the grid & time.

It works asynchronously — at any given moment it will usually have evolved different parts of the pattern through different numbers of generations.

The algorithm doesn't come without its drawbacks. For instance it's a very memory intensive implementation, since it has to potentially create multiple versions of the grid to cache the results. As such it is not suitable for showing a continuous display of the evolution of a pattern. Moreover, HashLife performs poorly on highly chaotic patterns, since there is nothing for it to memorize, so switching to other alternatives like QuickLife are preferred.

We'll first focus on (1) reducing space via Quadtrees, then move to (2) reducing time via memoization. There will also be a section on achieving Hyperspeed using properties discovered through the algorithm's implementation.

Reducing Space

Redundancy in Patterns?

After exploring CGOL for some time, you may notice that there are "repeating" configurations (e.g. oscillators + still-lives). One step further, consider how large patterns can lead to subpatterns that appear in several places, possibly at different times. This is what Hashlife answers.

Quadtree

A quadtree is a tree with exactly four nodes. Similar to a binary tree, quadtrees are often used for automata + image manipulation.

We can think of a quadtree as quadrants on a 2D grid. When we think of a graph, we know that there are four quadrants that surround the X-Y axis. Think of each quadrant as its own subgraph. From here, each subgraph has its own quadrants, leading to subgraphs within subgraphs, and you get the idea.

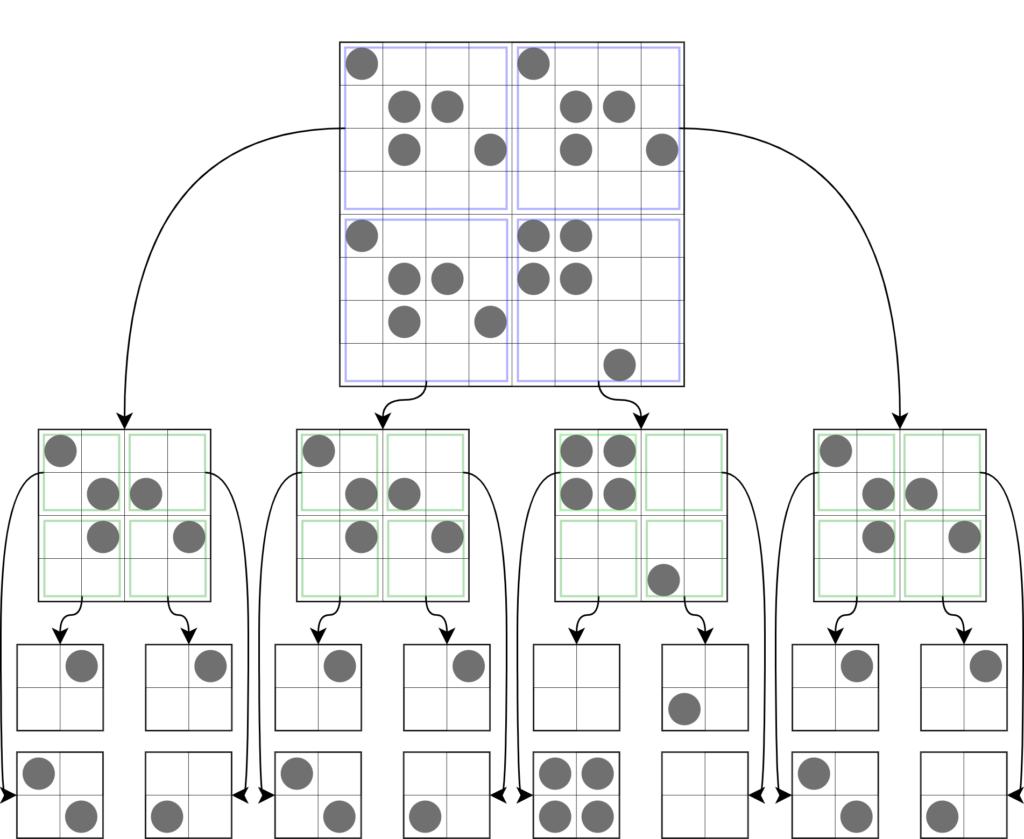

We can visualize this example through this:

In quadtrees, graphs/grids are referred to as nodes. Treat every node as it's own "configuration grid". Notice how each node holds a portion of the configuration of its parent node. Each level of the graph decreases by one as you move down the graph:

- For example, a level 1 node is a 2x2 grid.

- For example, a level 2 node is a 4x4 grid.

- For example, a level 3 node is a 8x8 grid.

- Notice that each new level can fit four nodes of the previous level. A level 2 node's 4x4 grid can hold exactly four 2x2 grids, or exactly four level 1 node.

- At level 0, it contains the exact pixel, or 1x1 grid.

Optimizations

Notice that in the previous representation of our quadtree, many nodes look exactly the same. This is a problem, because it's exhaustive-- we're not reusing these nodes, so we're actually increasing our space then decreasing it. Since the naive implementation uses the entire 2D grid to represent our configuration, we're not beating it in memory size. In fact, we store the 2D grid at the root node, in addition to the many subnodes under the quadtree. Therefore, we need some way to compress the tree so this tree representation can be more viable than a 2D grid.

We'll start by stating some observations from building out the exhaustive version of the quadtree:

1. In level 0, a 1x1 grid can only be black or white. Therefore, there are only two nodes at level 0.

- Furthermore, a 2x2 grid can only have 2^4 configurations, so there are only 16 nodes at level 1.

- Formulating this, the number of nodes is 2^(2^k * 2^k), where k is the level.

- Obviously, the number of configurations skyrockets as we move up the graph, but it is important to understand how small & feasible the lower levels are. In fact, we can consider them as "building blocks", or more formally "cardinal nodes".

2. The number of specific grids occuring is much lower. This is true, and we should NOT exhaust all possible grids. Therefore, we can treat the above optimization as a hard limit.

3. To maximize sharing a common grid, only create one instance of that grid in our quadtree. As you may observe from the image, there are 3 out of the 4 quadrants of the 8x8 grid that are exactly the same. If instead of creating a new node for each quadrant, we just simply point to one instance of that subnode, we can significantly decrease the amount of subnodes we create. Moving further, we can keep abusing this principle to decrease the size of our quadtree.

For the application, we can use hashing to map any grid to an existing grid on the quadtree, avoiding creating duplicates.

Below, each level may have subgrids that are already memorized by the previous level. For instance, the level 3 node has three subgrids that match the left level 2 node, and one subgrid that match the right level 2 node. This is our ideal quadtree-- tightly compressed!

Why not other implementations?

Simple implementation:

At each generation, use the neighbors of a cell to compute the next state.

Why is this bad?

It's O(kn), where n is the number of cells. Therefore, as we increase the number of cells, the algorithm will have to update every cell by a constant factor k. So, for sextillion cells, we'd have to make multiple sextillion updates!

Moreover, the representation of our grid is, well a grid! While it is the most intuitive way to represent our problem, there is no room to compress it, especially when we're encountering repetition that our grid just doesn't account for. Instead, we want to abuse pointers & caching in our representation, leading to the "quadtree".

Aside: Why representation is important:

Representation is key to reducing space. Remember, space is memory, and our desktop can only handle so much memory. For instance, "00000000" can be represented as "8#0" which is a smaller string!

For a "very dumb" example, if our grid was a 100x100 grid of all zeroes, then we can represent it as (100, 100, 0) instead of a 100x100 grid, reducing our space considerably.

That's why it's so important to focus on representation. It allows us to reduce a ridiculous amount of space to a smaller one, which can massively improve performance.

The Quadtree division:

With this representation, each of the four quadrants represents (nw, ne, sw, se). We can represent each grid as a Node, which we will showcase here:

class Node { /* * Four quadrants of a node. * * nw, ne, * sw, se * * At level one, each quadrant is either (0, 1). */ nw: Node | number; ne: Node | number; sw: Node | number; se: Node | number; // Current level of the node in the quadtree. level: number; constructor( nw: Node | number, ne: Node | number, sw: Node | number, se: Node | number ) { this.nw = nw; this.ne = ne; this.sw = sw; this.se = se; this.level = 0; if (typeof nw === "number" && typeof ne === "number" && typeof sw === "number" && typeof se === "number" ) { this.level = 1; // 2x2 } else if ( nw instanceof Node && ne instanceof Node && sw instanceof Node && se instanceof Node ) { this.level = nw.level + 1; } }

You'll notice that if the quadrants are at level one, they'll be a 1x1 grid of either 0 or 1, so we can represent them as a number rather than an entire Node. This distinction is useful to label each level, which you can see in our constructor.

Once we have the root node of a quadtree, we can now recursively update each level on the quadtree.

For example, given the 4x4 grid, we would have to compute directly on it, wasting time. Instead, we can segment the 4x4 grid to a "quadtree", breaking it down to smaller chunks. Then, we can work on the smaller chunks, and reassemble the 4x4 grid with the new updates ("divide-and-conquer").

In other words, we can represent any possible grid of any size down to a series of canonical blocks with a fixed set of configurations. For instance, we can choose the 2x2 grid to be our canonical block. Therefore, we consider all the possible 2×2 cell blocks, leading to 16 possible 2×2 blocks. With this, we perform the quadtree division until we reach lots of 2×2 blocks, then reconstruct the original matrixes with the updated versions of those 2x2 blocks.

🟥 Hold on. Isn't this no better than just working on the original grid?

Since we will already know all the possible updates of 16 2x2 blocks, we can just cache it in memory, and reuse them instead of computing the update ourselves. Therefore, we're working on a substantially smaller, compressed tree rather than the full grid.

function evolveNode(node) { if (node.level < 2) throw new Error('Current level cannot be less than 2.'); if ( !( this.nw instanceof Node && this.ne instanceof Node && this.sw instanceof Node && this.se instanceof Node ) ) throw new Error('Current node cannot be at depth 1.'); let resultNode; if (node.level === 2) { // Evolve via simple implementation. } else { resultNode = constructNode( evolveNode(node.nw), evolveNode(node.ne), evolveNode(node.sw), evolveNode(node.se), ); } return resultNode; }

🟥 Hold on. Won't the neighbors of any given node affect that node? In other words, is it feasible to run evolveNode() on the quadrants independently if they share neighbors between the quadrants?

Yes the neighbors will affect the node, so we will have to strategize some alternative solutions. The key idea is that updating the entire node is impossible without information from other nodes.

Alternative solutions:

- Consider the neighbor's contents towards updating a node -> redundant

- Pass the neighbor's pointers.

- Create a center node. Each result of

evolveNode()will return a subgrid, one level lower, centered at the original grid. For example, a 8x8 grid will return a 4x4 grid centered at the original 8x8.

Why doesn't Solution #1 or #2 work?

We would not be reducing the time if we incorporate all the neighbors when evolving a grid, so we need a solution that evolves a subgrid independently from its neighbors. Therefore, our solution must meet the original purpose at all costs.

Moreover, we don't need all of the neighbor's information. We just need enough so that each pixel on the grid has all eight neighbors.

With the third solution, we realize that the maximum possible subgrid that allows all eight neighbors for every cell is the center subgrid. In fact, the simplest subgrid to work on is the center subgrid.

Therefore, we will focus on Solution #3.

The result of evolve(node) will produce a center subgrid, one level down.

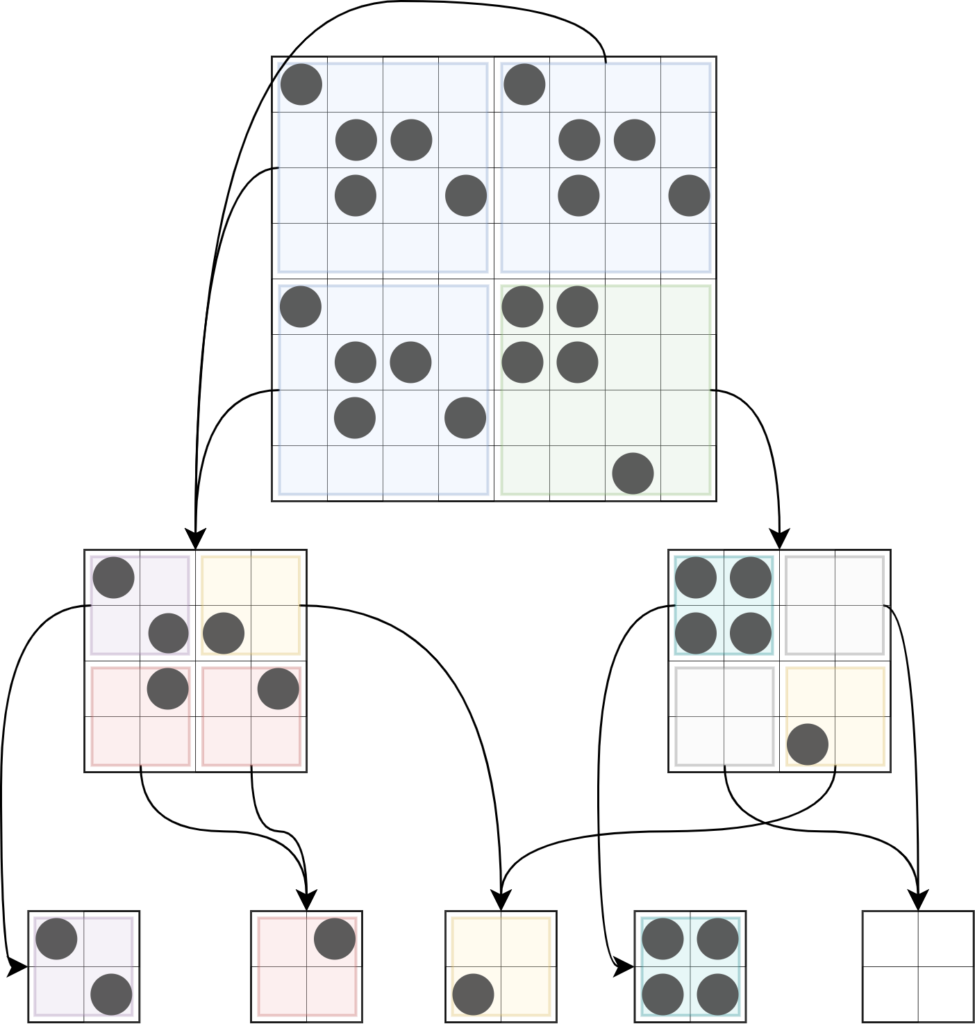

When we recurse, each subgrid will calculate its own center grid, which we can see in green.

We haven't considered the edges of the center grid, because we simply don't need to! Consider a fixed grid for Conway's Game of Life. On the edges of the grid, these cells cannot be determined, since they lack all eight neighbors to determine whether they can live or not.

To put it more rigorously, we CANNOT determine the result of the edges of the grid without the information found outside of the given grid. Since we are strictly working independently with our grid, we focus on determining the center grid, as we can guarentee the correct result.

When implementing, it's crucial the quadtree accomodates for the entire configuration. If the root node has edge cells that are active, then the tree is not sufficiantly large enough and must expand to accomodate for those cells.

However, notice how we can't construct the blue center grid with the green center grids because they're not completely aligned. Only a quarter of each green center grid fits in the center blue square. We're only capturing the corners of the blue center grid.

Looking closer, it may be feasible to construct the blue square if we found multiple green center grids that outline the perimeter of the blue square. This observation paves the way for the "nine auxillary squares" strategy.

Nine auxillary squares

// Second version. function evolveNode(node) { if (node.level < 2) throw new Error('Current level cannot be less than 2.'); if ( !( this.nw instanceof Node && this.ne instanceof Node && this.sw instanceof Node && this.se instanceof Node ) ) throw new Error('Current node cannot be at depth 1.'); let resultCenterNode; if (node.level === 2) { // Evolve via simple implementation. } else { const n00 = node.nw.centerNode(); const n01 = node.nw.centerHorizontalNode((east = this.ne)); const n02 = node.ne.centerNode(); const n10 = node.nw.centerVerticalNode((south = this.sw)); const n11 = node.centerNodeNode(); const n12 = node.ne.centerVerticalNode((south = this.se)); const n20 = node.sw.centerNode(); const n21 = node.sw.centerHorizontalNode((east = this.se)); const n22 = node.se.centerNode(); resultCenterNode = assembleNineNode( evolveNode(n00), evolveNode(n01), evolveNode(n02), evolveNode(n10), evolveNode(n11), evolveNode(n12), evolveNode(n20), evolveNode(n21), evolveNode(n22), ); } return resultCenterNode; } function centerNode() { return this.constructor.constructNode( this.nw.se, this.ne.sw, this.sw.ne, this.se.nw, ); } function centerHorizontalNode(east) { // Requires two nodes, the west ("this") & the east ("east"). return this.constructor.constructNode( this.ne.se, east.nw.sw, this.se.ne, east.sw.nw, ); } function centerVerticalNode(south) { // Requires two nodes, the north ("this") & the south ("south"). return this.constructor.constructNode( this.sw.se, this.se.sw, south.nw.ne, south.ne.nw, ); } function centerCenterNode() { // Like center node, but one more iteration. return this.constructor.constructNode( this.nw.se.se, this.ne.sw.sw, this.sw.ne.ne, this.se.nw.nw, ); }

A complication with this approach is that we'd have to create an entirely new function just to break apart these nine auxillary squares and get the portion we need to assemble the blue center square.

When constructing the original node, we can avoid breaking down the subgrids of each nine grids, and instead creating each of the four center quadrant grid of the blue grid.

Since the center blue grid has four quadrants, we can take the four surrounding auxillary grids for each quadrant, use our construct function to create our center grid, and then combine all these four quadrants together to form the final blue grid. Isn't that neat!

// Third version. function evolveNode(node) { if (node.level < 2) throw new Error('Current level cannot be less than 2.'); if ( !( this.nw instanceof Node && this.ne instanceof Node && this.sw instanceof Node && this.se instanceof Node ) ) throw new Error('Current node cannot be at depth 1.'); let resultCenterNode; if (node.level === 2) { // Evolve via simple implementation. } else { const n00 = node.nw.centerNode(); const n01 = node.nw.centerHorizontalNode((east = this.ne)); const n02 = node.ne.centerNode(); const n10 = node.nw.centerVerticalNode((south = this.sw)); const n11 = node.centerNodeNode(); const n12 = node.ne.centerVerticalNode((south = this.se)); const n20 = node.sw.centerNode(); const n21 = node.sw.centerHorizontalNode((east = this.se)); const n22 = node.se.centerNode(); const center_nw = constructNode( evolveNode(n00), evolveNode(n01), evolveNode(n10), evolveNode(n11), ); const center_ne = constructNode( evolveNode(n01), evolveNode(n02), evolveNode(n11), evolveNode(n12), ); const center_sw = constructNode( evolveNode(n10), evolveNode(n11), evolveNode(n20), evolveNode(n21), ); const center_se = constructNode( evolveNode(n11), evolveNode(n12), evolveNode(n21), evolveNode(n22), ); resultCenterNode = constructNode( center_nw.centerNode(), center_ne.centerNode(), center_sw.centerNode(), center_se.centerNode(), ); } return resultCenterNode; } function centerNode() { return this.constructor.constructNode( this.nw.se, this.ne.sw, this.sw.ne, this.se.nw, ); } function centerHorizontalNode(east) { // Requires two nodes, the west ("this") & the east ("east"). return this.constructor.constructNode( this.ne.se, east.nw.sw, this.se.ne, east.sw.nw, ); } function centerVerticalNode(south) { // Requires two nodes, the north ("this") & the south ("south"). return this.constructor.constructNode( this.sw.se, this.se.sw, south.nw.ne, south.ne.nw, ); } function centerCenterNode() { // Like center node, but one more iteration. return this.constructor.constructNode( this.nw.se.se, this.ne.sw.sw, this.sw.ne.ne, this.se.nw.nw, ); }

Reducing Time

Memoization

We can cache each result of evolveNode() so everytime we reach the same parameters, return the cached result from a hash table.

To visualize the significance of this, imagine our pattern evolves in a circular loop, arriving at its original configuration in N steps. If we cache each N iteration, we can return the result instantly for any future iterations ("exploding effect").

// A simple demonstration. const cache = { // [grid]: centerGrid, or more specifically: // [node]: evolve(node) };

However, hash tables cannot "hash" a node, since it only hash primitives (int, float, etc.) + strings. Therefore, we need to convert a grid to a "hash", and ensure that it is unique to that grid.

The simplest approach is to use the pointer address, since our quadtree only has one instance of each grid, so all pointers pointing to it will have the exact same address. But, since the center nodes were originally mis-aligned with the original center node, they will result in different patterns, and thus different hashes. To alleviate this, we can make our hash a combination of the subnodes.

In my implementation in Typescript, it's much easier to use a randomized ID, so I opted for UUIDv4. Of course, as long as your hash is as unique as possible, any implementation will work.

Achieving Hyperspeed

Instead of grabbing the centers, why don't we just call evolveNode()?

Wouldn't it just increase our time complexity? Well, yeah!

But at the same time, we're using memoization, so we're caching significantly more since we're evolving twice. This is the key to hyperspeed.

For a 8x8 node, we evolve nine 4x4 nodes, then evolve those. Two evolutions. For a 16x16 node, we evolve nine 8x8 nodes, then evolve those. Since we established that the 8x8 nodes will have two evolutions, then we'll essentially achieve four evolutions.

In summary, at each higher depth, we double the evolutions, all of which is cached immediately!

// Fourth version. function evolveNode(node) { if (node.level < 2) throw new Error('Current level cannot be less than 2.'); if ( !( this.nw instanceof Node && this.ne instanceof Node && this.sw instanceof Node && this.se instanceof Node ) ) throw new Error('Current node cannot be at depth 1.'); let resultCenterNode; if (node.level === 2) { // Evolve via simple implementation. } else { const n00 = node.nw.centerNode(); const n01 = node.nw.centerHorizontalNode((east = this.ne)); const n02 = node.ne.centerNode(); const n10 = node.nw.centerVerticalNode((south = this.sw)); const n11 = node.centerNodeNode(); const n12 = node.ne.centerVerticalNode((south = this.se)); const n20 = node.sw.centerNode(); const n21 = node.sw.centerHorizontalNode((east = this.se)); const n22 = node.se.centerNode(); const center_nw = constructNode( evolveNode(n00), evolveNode(n01), evolveNode(n10), evolveNode(n11), ); const center_ne = constructNode( evolveNode(n01), evolveNode(n02), evolveNode(n11), evolveNode(n12), ); const center_sw = constructNode( evolveNode(n10), evolveNode(n11), evolveNode(n20), evolveNode(n21), ); const center_se = constructNode( evolveNode(n11), evolveNode(n12), evolveNode(n21), evolveNode(n22), ); resultCenterNode = constructNode( evolveNode(center_nw), evolveNode(center_ne), evolveNode(center_sw), evolveNode(center_se), ); } return resultCenterNode; } function centerNode() { return this.constructor.constructNode( this.nw.se, this.ne.sw, this.sw.ne, this.se.nw, ); } function centerHorizontalNode(east) { // Requires two nodes, the west ("this") & the east ("east"). return this.constructor.constructNode( this.ne.se, east.nw.sw, this.se.ne, east.sw.nw, ); } function centerVerticalNode(south) { // Requires two nodes, the north ("this") & the south ("south"). return this.constructor.constructNode( this.sw.se, this.se.sw, south.nw.ne, south.ne.nw, ); } function centerCenterNode() { // Like center node, but one more iteration. return this.constructor.constructNode( this.nw.se.se, this.ne.sw.sw, this.sw.ne.ne, this.se.nw.nw, ); }

The Beauty of Hashlife

Despite how difficult the algorithm may pose to be at first, especially when arriving at these properties unique to the Game of Life, one may ponder at just how simple & elegant the final solution is.

It's a testament to the simplicity of recursion-- iterating over itself through smaller and smaller subtasks until we arrive at a solution. By allowing our algorithm to divide the work to smaller pieces, we can repeat repetitive work (such as applying the Conway's rules) to multiple smaller subgrids, re-assembling it to the original grid.

Moreover, it's astonishing how by just adding one more evolveNode() to our recursive function, we can dramatically increase the rate of iterations, which is only beneficial since we cache everything into memory.

It's like trying to build a gigantic Lego set from the ground-up, focusing on the fundamental pieces we know and love, and tackling a large feat through this foundation. HashLife is a brilliant takeaway to how we achieve success through formidable tasks by breaking down such tasks to more managable pieces.

There are so many implementation details we haven't discussed:

- How do you expand the quadtree to fit a large configuration?

- How do you retrieve a particular cell from the quadtree structure?

- How do you retrieve all cells from the quadtree structure?

- How do you set a particular cell from the quadtree structure?

- How do you move to the Nth step?

But alas, this article is already too exhaustive, and it's up to you to discover these solutions yourself. To see the full code, you can check out my Github repo. Again for those wondering, if you'd like to play & experiment with Conway's Game of Life with the HashLife implementation, feel free to visit the web application. You can see it in full action by changing the step size (or, speed) through the top-bar.

However, as mentioned in the beginning, Hashlife has an unbearably slow start before it begins its exploding period. Moreover, patterns with random growth are not compatible with Hashlife because the algorithm fails to cache any repeating patterns.

Sources

All resources, whether for learning or information, are sourced here. Most of the images & diagrams I've used can be found through these websites. Please take a look at them! Without the wealth of knowledge from these articles, I wouldn't have arrived at the solution for this particular project.

HashLife at Official Wikipedia -- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hashlife

HashLife at Official LifeWiki -- https://conwaylife.com/wiki/HashLife

An Algorithm for Compressing Time and Space -- https://www.drdobbs.com/jvm/an-algorithm-for-compressing-space-and-t/184406478

HashLife by ninguem -- https://www.dev-mind.blog/hashlife/

Get a Life by Ben Lynn -- https://xenon.stanford.edu/~blynn/haskell/life.html

--

You've reached the end, thank you for reading. To stay notified, consider checking out my RSS to be notified of articles like this-- it may be worth your time!

Have a comment, question, or an ask? Feel free to email me!